At 7:20 a.m., Otakanomori Station is located in Nagareyama City, Chiba Prefecture, about 25 kilometers from downtown Tokyo. At the Otakanomori Nursery Station on the third floor of the Leifgaden Building, about 20 meters away, the greeting “Ohio Gojaimas (hello)” was heard every two minutes. For about 20 minutes, fathers and mothers constantly walked in, hugging or holding hands with one or two children. Parents who left their children walked through aisles directly connected to the station and loaded themselves onto the train. This place is a different “childcare station” from ordinary daycare centers. At 8 a.m., when their parents finished their work, the children took the bus back to 102 daycare centers in Nagareyama City. After spending the day, they returned to the nursery station again at 4-6 p.m. to meet their parents who left work by subway and go home. Nagareyama, a bedtown in Tokyo, is a city where the population is growing every year even in Japan, which is struggling with low birthrates. By 2022, the Japanese government had ranked first among 772 cities in population growth for the sixth consecutive year. The population last year was 209,237, an increase of about 40,000 from 168,024 in 2013. The number of children aged 0 to 9 increased from 16,194 to 24,169 during the same period. The total fertility rate is 1.56, which is more than the Japanese average of 1.26. Japan’s Institute for Social Security Population Studies estimated that the city’s population will increase to 241,000 by 2050. “Among the roles of local governments, childcare facilities are the most basic and essential infrastructure,” said Kawajiri, marketing director of Nagareyama City.

Nagareyama City has increased the number of daycare centers by six-fold from 17 in 2010 to 102 by last year. In 2017, the number of waiting children at daycare centers reached zero (0 children). In this city, dual-income couples do not have enough childcare centers to care for their children. For dual-income couples, the daycare center they want is far away, or daycare centers around their homes are often filled early.

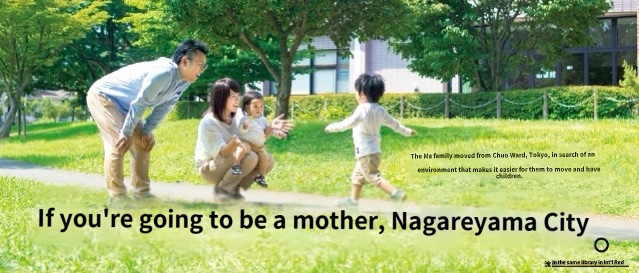

Nagareyama City has set up “childcare stations” at two major subway stations bound for Tokyo to solve the problem. A “station daycare center” was set up at the station to allow the children to leave their child behind on their way to and from work. If your home is more than 500 meters away from the daycare center, you can use the child care station. The fare is 2,000 yen (about 18,000 won) per month, which is cheap. If you get off work late, you can take care of your child until 8 p.m. at the daycare center. Dinner is also provided to parents and children. It costs 400 yen (about 3,600 won). “It is not easy for a working mother to take care of her child when she gets off work late, but we prepare it like a home-cooked meal for her so that she does not feel guilty about not having prepared a meal for her,” said an official at the Otakanomori nursery station. “The nursery station relieved parents of the stress of having to take their child to the daycare center every morning and the stress of bringing them home when they are late,” said Diamond, a Japanese weekly magazine. “It is effective to reduce the time of commuting to and from work.” Nagareyama’s success story has spread to neighboring cities, and 35 Japanese cities have now created child care stations right next to the subway station. What if her child enters elementary school. Nagareyama City plans to go beyond the “wall of the first elementary school” following the daycare center. Children who enter elementary school often go to school later and come earlier than when they are at daycare center. Double-income couples need a place to leave their children for about one hour in the morning and three to four hours in the afternoon. Nagareyama City operates one to three after-school classes at all 17 elementary schools in the city. In the case of Otakaso School, there are many students who want to attend, so they cooperate with each other with one after-school classroom at the school and two outside the school. For example, they do after-school activities at the school twice a week and at private academies three times a week. Through this cooperative system, parents leave their children until 8 p.m. If desired, all first to third graders in elementary school can use after-school classes without waiting. As the fertility rate rises, the city’s appearance is changing, too. With the number of children aged 0 to 9 reaching 24,000, more than 30 pediatric hospitals have been built in small cities with a population of 200,000. With competition gaining ground, some pediatricians are now operating on weekends or at night. There are also more parks and playgrounds where young parents can take their children. Around 50 children from daycare centers were running around at Nishihatsuishi Park near Otakanomori Station on the day. About 10 people wearing yellow hats built sand castles in the park’s sand field, and the children with pink hats played tag. Next to them, about 20 elderly people in their 70s were enjoying gateball. Garube, in his 30s, a mother of two, said, “When children go to the playground, they get along well with many children their age,” adding, “I’m thinking about whether to give birth to a third child.”

JULIE KIM

US ASIA JOURNAL