As Seoul, Washington and Tokyo seek tougher punitive measures for Pyongyang’s recent nuclear test, attention is being focused on what sanctions will be included in a fresh U.N. Security Council resolution.

The three governments have agreed to push for “new, meaningful” sanctions, noting that they can no longer take a “business-as-usual” approach to the communist regime in the wake of its self-proclaimed hydrogen bomb test last Wednesday.

A Security Council diplomat told the Associated Press that the UNSC is working on a resolution that imposes tougher sanctions on the North for the latest nuclear test, which is “a step change” from its three previous atomic tests in 2006, 2009 and 2013.

The unnamed diplomat said all 15 Security Council members agreed that the North should be denuclearized, and this will be reflected in a new resolution.

Seoul officials said the UNSC would explore ways to strengthen the enforcement of existing UNSC sanctions resolutions or seeking fresh sanctions, in line with its previous pledge to take “further significant measures” in the event of Pyongyang’s additional nuclear test.

They refused to elaborate on the details of the sanctions amid ongoing negotiations over them.

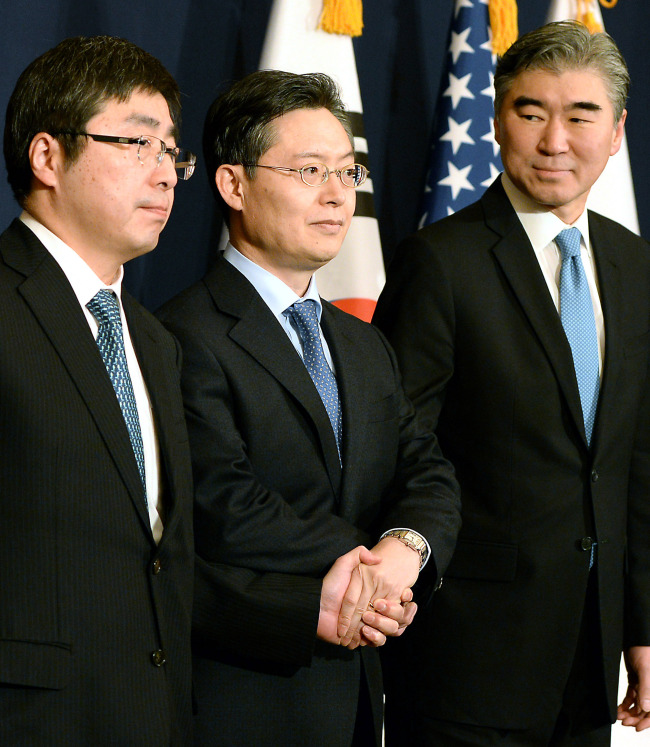

“South Korea, the U.S. and Japan have decided to concentrate diplomatic efforts on ensuring that the UNSC will adopt a resolution of strong and comprehensive sanctions,” Hwang Joon-kook, South Korea’s chief nuclear envoy, told reporters following his trilateral talks with his U.S. and Japanese counterparts, Sung Kim and Kimihiro Ishikane respectively, on Wednesday in Seoul.

“We will continue our close communication and cooperation with China and Russia.”

The existing sanction resolutions 1718, 1874, 2087 and 2094, which were adopted to punish Pyongyang’s nuclear and long-range missile tests since 2006, involved arms embargoes, interdiction of North Korea-related cargo, financial sanctions and sanctions on particular individuals or entities including North Korean enterprises.

After the North’s first nuclear test in October 2006, the UNSC adopted Resolution 1718 that bans Pyongyang’s additional nuclear and ballistic missile tests, and calls on it to abandon its nuclear program in a “complete, verifiable and irreversible” manner.

Following the second nuclear test in May 2009, Resolution 1874 was adopted to extend arms embargoes on the North, employ inspections of its cargo — on land, sea and air — and prevent any financial services to contribute to the North’s nuclear and missile program.

|

| Hwang Joon-kook (center), South Korea’s chief nuclear envoy, attends trilateral talks with his U.S. and Japanese counterparts, Sung Kim and Kimihiro Ishikane, respectively, on Wednesday in Seoul. Yonhap |

These anti-Pyongyang sanctions were further tightened in January 2013 when the UNSC adopted Resolution 2087 for the North’s long-range rocket test in December 2012. The resolution expanded the list of North Korean individuals and entities subject to international sanctions and strengthened the regulations for the interdiction of North Korean ships at high seas, among other things.

Following the third nuclear test in February 2013, the UNSC adopted Resolution 2094 that imposed tougher financial sanctions on the North, while tightening and expanding export embargoes on items that can potentially have military utility.

The last resolution also carries the “catch-all” provision that calls on states to prevent the supply, sale or transfer of any item that might contribute to Pyongyang’s activities prohibited under Security Council resolutions.

But it remains to be seen whether the strengthening of these sanctions would have a real impact on curbing the growth of Pyongyang’s nuclear program, given that the reclusive state continued to make progress in its nuclear and missile technology despite the sanctions.

China and Russia are expected to be a critical stumbling block to the efforts for tougher sanctions, given that they have called for restraint and caution and stressed their position against moves to escalate tensions with the North.

Some observers raised the possibility that to more effectively pressure the North to give up its nuclear arms, the UNSC could consider employing third-party sanctions, or a “secondary boycott” which would sanction any businesses or financial institution of a third country that engages in financial transactions with the North.

But Seoul officials think the secondary boycott is an unlikely scenario as it would not be effective for an isolated country like North Korea that has little trade or business relations with the outside country except for China.

Expectations have also been raised that Seoul and Washington could push for the so-called BDA-type sanctions that the U.S. slapped on the North in 2005. Washington sanctioned the Macau-based Banco Delta Asia bank, which managed some $25 million for Pyongyang, for purportedly helping the North launder illegally earned money.

Analysts, however, said the BDA-type sanctions might not work anymore, considering that the North has altered the way it manages its leader’s overseas funds to neutralize the effect of any such financial sanctions.

Apart from the UNSC multilateral sanctions, Seoul, Washington and Tokyo are exploring ways to apply individual sanctions against the North.

On Tuesday, the U.S. House of Representatives passed a North Korea sanctions bill sharpening punitive actions against the provocative regime.

This bill requires the U.S. president to investigate any credible information of suspicious activities involving the North and to designate and apply sanctions regarding any person or entities knowingly engaging in or contributing to activities in the North, through export or import, which involve weapons of mass destruction, related material, luxury goods, money laundering, censorship, or human rights abuses.

By Song Sang-ho (sshluck@heraldcorp.com)