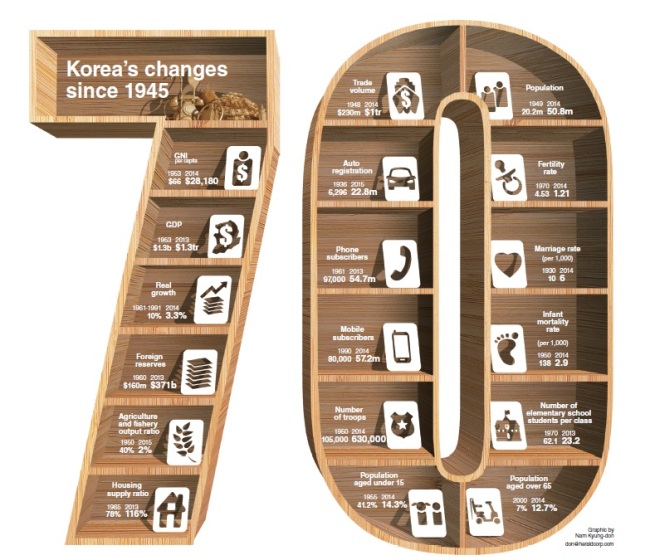

South Korea has achieved many great feats over the last seven decades in political and socioeconomic areas since it gained independence.

Its economy, with per capita income much smaller than that of African countries such as Ghana and Gabon in the aftermath of the inter-Korean conflict, was able to grow rapidly through policies that promoted technology, manufacturing and exports, in order to develop from farming and fishing.

Once a poor country that relied on development aid, Korea emerged from its ruins and ashes of Japan’s colonization and war with North Korea, with the “Miracle on the Han River” growth model now being shared with the world.

The country is the world’s 13th-largest economy, with the total value of its output growing from $1.3 billion in 1953 to more than $1.4 trillion in 2014. It has one of the fastest broadband penetration and mobile connection rates, and has a high education rate with more than 70 percent of high school students going to college. Part of the OECD and the G20, Asia’s fourth-largest economy is home to world’s most competitive industries and conglomerates ― automobiles, shipbuilding, semiconductors, electronic appliances, construction and chemicals.

It had gone through a series of abrupt and unstable political systems, with many people sacrificing their lives for democracy. But the country is known for adopting democracy and universal suffrage in a short period of time.

“The country was able to use its alliance with the U.S. to strengthen its sovereignty and security, at the same time successfully modernize its industries,” said professor Park Ihn-Hwi of Ewha Womans University’s Graduate School of International Studies.

It ranks in the top 10 in both summer and winter sports, with Korean music and dramas igniting the world’s interest in the country’s K-pop culture.

But the rapid growth, which mainly benefited the very richest, has fueled inequality, especially after the Asian financial crisis in the late 1990s, while the prolonged division between the two Koreas has left South Korea alone to “half-celebrate” its accomplishments and the 70th Liberation Day.

“South Korea has achieved many remarkable results except for the most important thing ― reunification with the North,” said Choi Jin-woo, president of the Korean Political Science Association.

“Our true liberation can only be celebrated when the two Koreas reunite.”

Kim Young-rae, honorary professor at Ajou University, said that inequality poses a downside risk to South Korea, which faces a low birth rate, high youth unemployment and a rapidly aging population as a result of its policies that disproportionately favor conglomerates.

With the political process based on the interest of politicians rather than that of the people, Korea has become an “angry society” with a growing number of people having little or no faith in the system.

“Our economic and living standards have improved, but can we say the same thing in terms of quality? There is a huge gap between the meaning of ‘hope’ we felt in the 1960s and the one we feel now,” said Kim, a former president of Dongduk Women’s University.

“Korea needs to develop a sustainable wealth redistribution policy that can help create equal opportunities for the low income group, small and medium enterprises and nonregular employees.”

In addition to renewing its growth model that can spur innovation rather than following or catching up with advanced economies, the two Koreas need to push efforts to normalize their relations.

Reunification will be able to bring forth new opportunities that will enable South Korea to overcome low growth and create a “new miracle on the Korean peninsula.”

Professor Son Key-young of the Asiatic Research Institute of Korea University said the future of this country will rely on how it will be able to resolve inequality and conflicts with the North.

“They will be the two biggest issues facing South Korea in the 21st century, and how we tackle them will shape how we will become (a new) Korea,” said Son.

By Park Hyong-ki (hkp@heraldcorp.com)