South Koreans who never attended middle school have a 5.2 times higher mortality rate than those who received higher education, a study showed Monday.

According to the study by the Korea Institute for the Health and Social Affairs, those who are poor and less educated are more likely to live shorter lives, are more vulnerable to car accidents and cancer, and have limited access to high-quality health care services.

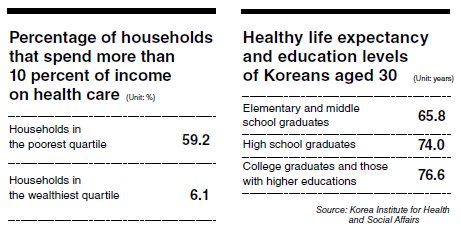

Among households that belong to the poorest 25 percent of the population, 59.2 percent of them spent more than 10 percent of their total income on health care in 2012. Meanwhile, only 6.1 percent of households that belong to the wealthiest 25 percent did the same.

Also, 7.5 percent of the poorest households could not receive necessary medical treatment for financial reasons, while only 0.6 percent of those who belong to the wealthiest 25 percent experienced such difficulties in 2012.

The healthy life expectancies ― average number of years that a person can expect to live in “full health” ― of Koreans aged 30 also varied according to their education levels. The rate among those who received higher education was 76.6, compared to 65.8 for those who never finished high school.

The study also showed that the poor had less access to cancer screenings. While 80.5 percent of the poorest 25 percent of Korean women received cervical cancer screening in 2012, 90.1 percent of the wealthiest 25 percent had their checkup.

Also, only 57.2 percent of Koreans who belong to the poorest 25 percent received colorectal cancer screening in the same year, while 67 percent of the wealthiest group received the examination.

The World Health Organization states that social factors including education, employment status, income level, gender and ethnicity have an influence on one’s physical and mental health. The lower a person’s socioeconomic position, the higher their risk of poor health, it says.

Kim Dong-jin, who organized the research at KIHASA, said the government should make efforts to combat health inequalities, which he thinks have been deepening in the last few years.

“Central and municipal governments should make joint efforts to monitor the situation consistently and archive the information,” he said. “There should be more policies and welfare programs to tackle this issue.”

By Claire Lee (dyc@heraldcorp.com)