This is the first article in a series on foreigners working in Korea’s technology start-up ecosystem. ― Ed.

With the world’s best broadband networks, global technology giants, game-crazy smartphone users and a hefty 4 trillion won ($3.7 billion) government budget to foster the local start-up ecosystem, Korea is building itself up to be the next major Asian tech hub.

But on the ground level, financial, legal, language and cultural roadblocks in Korea are still pushing many foreign tech entrepreneurs to favor Singapore or Hong Kong, industry experts say.

Statistics on the number of foreigner-owned technology-based start-ups in Korea are not readily available, but the Ministry of Justice said four people have received the technology start-up visa since its creation in October 2013 as of March. By comparison, over 30,000 ventures were newly incorporated in Korea last year.

|

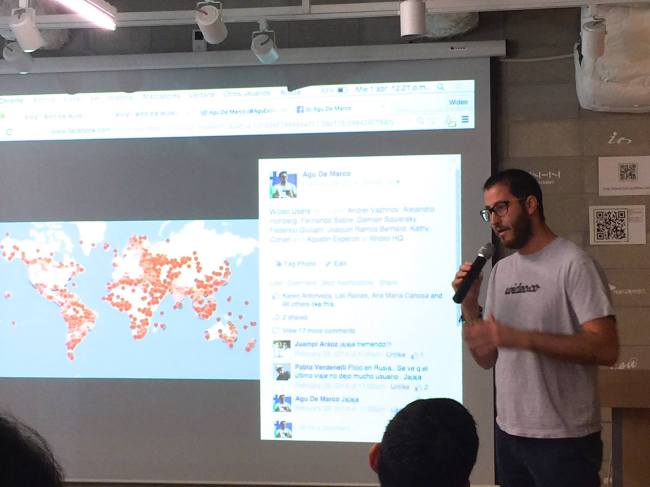

| Agu De Marco, CEO of Argentina-based start-up Wideo, speaks at Startup Alliance in southern Seoul last month. (Wideo) |

Lim Jung-wook, managing director of southern Seoul-based Startup Alliance, which connects local start-ups with other organizations, said the creativity that flourishes in global hubs such as Silicon Valley in the U.S. and Israel’s Tel Aviv are borne from a melting pot of ideas. This environment is largely absent in Korea, which has little immigration and a top-down work hierarchy, he added.

“Every time I visited those (tech hubs), I realized that … mixing people from different backgrounds, different races and different experiences helps them to have more innovative thinking,” said Lim, who studied and worked in the U.S. for five years and advocates flattening the workplace power structure.

“After I came back to Korea, I realized we need more diversity here, but it’s not that easy because of the language, our closed culture and employment issues.”

Despite the world-leading technology advancements of Korean global giants like Samsung and LG, Korea’s start-up ecosystem is considered emerging.

The Park Geun-hye government heralded its creative economy drive in 2013 to foster job creation, with a 3.31 trillion won push for start-ups to mend high youth unemployment via a new growth engine. The Small and Medium Business Association earmarked 3.9 trillion won in 2014 and 4 trillion won this year to support start-ups.

The SMBA’s Korea Institute for Startup and Entrepreneurship Development, which leads global start-up programs, set aside 3 billionwon in 2014 and 3.3 billion won this year on outbound programs to introduce Korean startups to overseas businesses in hubs like Shanghai and Silicon Valley. Other government agencies have similar outbound programs.

But Lim suggested that officialsare hesitant to drum up support for inbound programs for foreigners in Korea, for fear of public criticism that they are spending money on them when the youth unemployment rate is still high, hovering above 11 percent this year, according to Statistics Korea.

“Sometimes I mention to government officials that it is also very important to bring talent from outside and let them mingle with Korean start-up people, and that actually helps Korean start-ups to go global,” he said. “They appear to agree, but (implementing) a written policy is not that easy because they are afraid it could backfire.

“I think that’s really short-sighted and we need to overcome that kind of closed mindset.”

Foreign entrepreneurs argue that the hurdles to do business in Korea are too high: On top of language barriers, hard-to-reach angel and venture capital funds and swaths of red tape, many find operating impossible without a local partner.

Additionally, opening a tech startup previously required a $100,000 investment or an intellectual property patent until last year to secure a business visa, and current labor laws make it impossible to hire a foreign worker without hiring five full-time Koreans first.

Nonetheless, there has been a growing desire to get involved in the tech industry here, according to Alexander Bezzubov, an organizer of Seoul Tech Society, an Englishlanguage group for tech enthusiasts.

“I was actually impressed with how many foreigners are doing tech-related things here. It wasn’t like that three years ago,” he said. The network has grown from five members to 1,500 in two years, he noted, many of whom are foreigners working in both big and small companies as engineers, designers or entrepreneurs.

However, another barrier prevents them from integrating with the local scene: Korea is teeming with small, diverse tech communities, but they are insular and secretive to outsiders, Bezzubov claimed.

“There are a lot of (technology) communities in Korea. But all of them have 20-30 people, they’re closed, they don’t announce what’s going on and they’re all in Korean, of course, even though … they’re mostly discussing things related to material that is available in English,” he said, adding that STS was formed as an open network to fill this gap. “There’s a barrier you cannot cross, and language makes this barrier even harder.”

David Park, founder of KOISRA, which assists global-bound Korean and Israeli start-ups, said some Korean start-ups are similarly closed off. As “frogs in the well” that focus only on their immediate market, they consequently lose out on overseas mentoring and insights to be globally competitive, he said.

Diversity will be increasingly important for the local industry’s push from the saturated hardware market toward software advancements, which require creative, outof- the-well innovations, he added.

“If there’s no diversity, there’s no healthy start-up ecosystem, so I think the government should focus more on how to combine Korean entrepreneurs with foreigners,” Park said.

He suggested inviting foreign tech pros to participate in competitions, which could inspire local entrepreneurs to study and adapt new technologies.

“Now is the time to focus on software and people themselves,” he said.

The shift to software is accelerating with the growing popularity of the Internet of Things and a decline in hardware profitability, and industry experts say Korea is seeing a wave of change as people become more willing to take risks and start a business. Seasoned developers from conglomerates are using their experience to launch new companies, and young people who have studied abroad are gaining global ambitions, Park added.

Foreign entrepreneurs and developers also note that small and medium-sized Korean businesses are increasingly interested in working with them.

To integrate them, the change is trickling from the top. Last year, the SMBA kicked off a 2 billion won support project, and the Ministry of Justice created exemptions to the $100,000 investment requirement for foreign tech start-ups to receive the D-8 business visa.

The Ministry of ICT, which spearheads the government’s creative economy drive, told The Korea Herald it has begun researching how to diversify the local start-up community.

Private incubators are also warming up to foreign start-ups. With a wish to become a “pan-Asian platform for start-ups,” Google’s new Campus Seoul ― which launches Friday as the global tech giant’s first entrepreneur support space in Asia ― claimed more than 20 percent of its members are foreigners, according to its head Jeffrey Lim.

For Argentina-based start-up Wideo, which provides a userfriendly video-making platform, Korea edged out Singapore to become its Asian jump-off point this year due to the country’s bigger market size. CEO Agu De Marco said he is confident Wideo canadapt its product to Korean users, but is concerned about how unreceptive the local market is to familiar global names.

Social media giants Facebook and Twitter have gained local dominance, and Evernote and Amazon’s cloud service have made a notable landing, Lim of Startup Alliance said. But Yahoo dropped out of Korea in 2012, Google has only recently begun to eat away at Naver and Daum’s search engine market share, and local giants similarly dominate other tech sectors.

The overseas start-up presence is less clear. Even months of feasibility research could not give Wideo much insight on how to adapt its product, as few foreign tech startups have succeeded in penetrating

the Naver nation, De Marco noted.

“There’s something we’re not seeing, because if things were a bit easier, we would have seen more American start-ups or Western start-ups,” the Wideo chief said. “But that is something we’ll figure out.”

By Elaine Ramirez (elaine@heraldcorp.com)

Stephanie McDonald and Sang Youn-joo contributed to this report. ― Ed.