Rumors of a “ramen crisis” are rising in Japan, which is struggling amid high prices. Ramen restaurants are on the verge of bankruptcy after failing to overcome the “wall of 1,000 yen.” Ramen, Japan’s representative common people’s food, has an unwritten rule of “less than 1,000 yen a bowl.” In fact, according to the Tokyo Statistical Yearbook, the average price of ramen has hardly risen from 548 yen in 2000 to 567 yen in 2023. Ramen restaurants, which cannot raise food prices that much while prices are rising, are in crisis.

Imperial Data Bank, a market research firm, announced that 72 corporate ramen chains went bankrupt last year. The number of cases surged by about 30% from the previous year, compared to 53 cases, the highest ever. It is estimated that there are 500 to 1,000 corporate ramen chains in Japan. In other words, one or two out of ten ramen chains have closed. The statistics show that self-employed people’s local ramen restaurants are not closed, so in reality, it is estimated that much more ramen restaurants are in crisis. In a survey of the performance of 350 corporate ramen chains (2023), 61.5% of them were in a state of deteriorating business, with 33.8% of “deficit” and 27.7% of “profit decline.” It is the second most difficult situation ever after 2020 (81%) when the coronavirus hit the brunt.

The crisis of ramen noodles is largely due to the inflation rate of around 2 percent that the Japanese have never experienced before. The cost of ingredients for ramen has increased by 10 to 15 percent in the past two years. At one point, the price of pork skyrocketed 40 percent year-on-year last year. The minimum wage of pork also jumped 4.5 percent year-on-year to 1,163 yen per hour (based on Tokyo) from October last year. If the price of ramen is raised to 600 to 800 yen, it will be hard to avoid a deficit. Even so, if the price rises above 1,000 yen, customers who say, “Even ramen” may be ignored. In the Japanese ramen market, even if the price rises by 1 million yen, there is a high risk that a customer will be taken away from the next door. In fact, there are six to seven ramen restaurants within a 20-meter radius around Jinbocho.

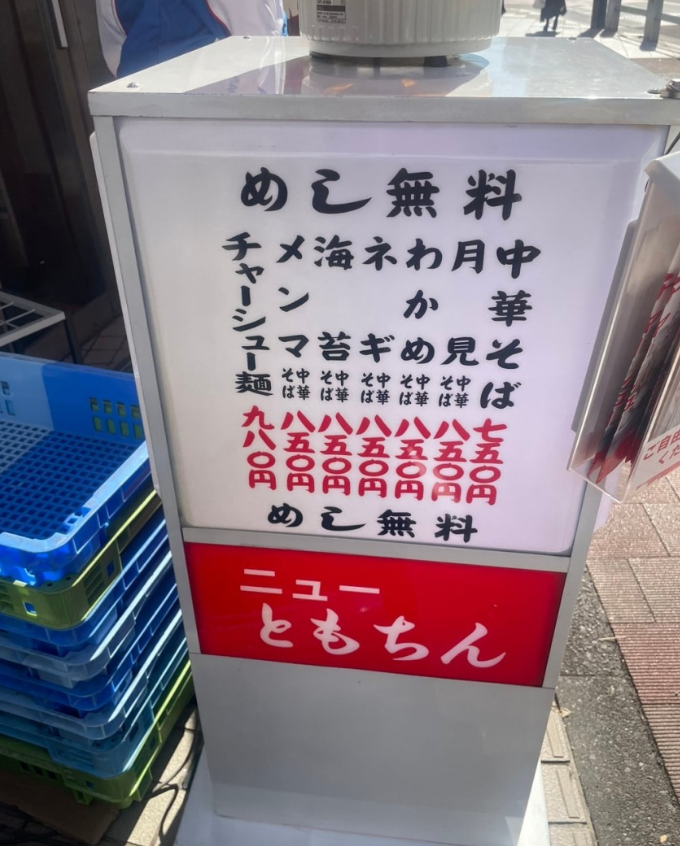

Some popular ramen restaurants have broken the 1,000-yen mark. Sanmaro Tokyo branch in Kanda, Tokyo costs 1,300 yen for salt ramen and 1,100 yen for Hakata Ramen, a popular franchise. Fujita’s tsukemen (ramen dipped in soup) also cost 1,100 yen. Ramen jibbit, a popular ramen restaurant that can be eaten in a line for an hour, sells a 500-yen “first pass.” It means that the restaurant pays an additional 500 yen for direct admission without queuing up.

It is a dream story for a local ramen restaurant. “If the price of ramen is over 1,000 yen, customers tend to stop visiting,” said Imperial Data Bank. “It is highly likely that bankruptcy will increase further this year, especially for small and medium-sized ramen restaurants.”

Consumers cannot afford to buy a bowl of ramen without hesitation. This is because the cost of food has increased significantly in most cases, including ramen. Food expenses for a three-member Japanese family recorded an average of 93,130 yen (93,130 yen) in August last year, up 16 percent from three years ago. Excluding December when food expenses increased, the figure is an all-time high. Compared to two years ago, most food ingredients including potato (53%), cucumber (39%) and lettuce (34%) rose more than 10 percent. The Engel index, which refers to the ratio of food expenditure among living expenses, is 30.4 percent, the highest in 42 years. Korea’s Engel index stands at 12.8 percent (2021).

The Nihon Keizai Shimbun reported, “Consumers are saving as the amount of beef purchased per household in Japan (August 2024) decreased by 6% and pork by 2% year-on-year. If the Engel index continues to be so high, they will have no choice but to cut spending on entertainment and durable goods.” This means that there could be a vicious cycle in various sectors of the economy. Ramen’s crisis is not a crisis unique to ramen restaurants, but a crisis for Japanese households that have become vulnerable.

SALLY LEE

US ASIA JOURNAL