Preventing the disappearance of provincial cities and slowing down the pace of population decline are not the only concerns in Korea. The Japanese Cabinet Office’s Regional Development Promotion Bureau, which had been seeking to “revive local 創” for the past 10 years, analyzed local governments across the country on Thursday and analyzed that four factors are successful factors in slowing the population decline: transportation, migration support, childcare support and corporate attraction.

Japan’s population was about 124 million as of last year, down about 600,000 from the previous year. However, not a few local governments have seen their population decline slow. Compared to the 2020 population estimate estimated in 2013, 736 local governments have increased their population. Excluding the metropolitan area, 610 local governments have increased their population by more than 5% from the estimate, reaching 102.

In this regard, the Japanese government analyzed that good transportation access (51 places), childcare support (33), migration and employment support (21 places), and corporate attraction (18 places) contributed to the population growth of local cities.

The city of Tsukuba Mirai (つくばみらい) in Ibaraki Prefecture was cited as a representative place where the population has increased only by reducing traffic inconvenience. The city changed with the opening of the new city railway “Tsukuba Express” in 2005, which can reach Akihabara Station in downtown Tokyo in about 40 minutes. As the younger generation who raise children began to move in as it became possible to commute to and from the city center, the population increased from about 40,000 in 2005 to 53,477 in June this year.

In some cases, child-rearing assistance programs saved the city. Nagareyama City in Chiba Prefecture is a case in point. For dual-income parents commuting to and from work, local governments provide support for a daycare center called “Songyeong (送迎) service.” When a child is entrusted to a Songyeong childcare station in front of the station on the way to work, the child can be taken to the daycare center on their own and brought back in the evening so that parents can easily take the child on their way home from work. The population of Nagareyama City is still increasing to the extent that two elementary schools need to be newly established. As of June this year, the population stood at 212,394, an increase of 1,761 from the same month last year.

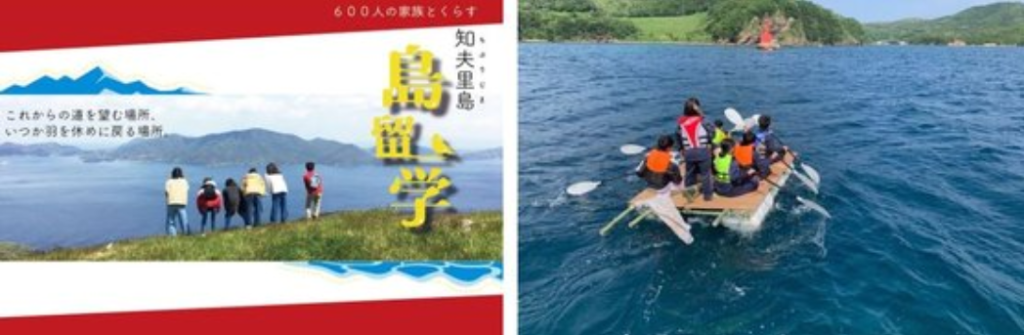

In some cases, the city has regained vitality as local governments worked to relocate and find jobs. Chibimura, Shimane Prefecture, is a small island with an area of only 14 square kilometers and had a population of only 657 people in 2010. The idea for people to migrate was to “study on an island.” It allowed children between fifth and third graders to study in natural environment, slowing down the population decline. As the government recently introduced a system for young people in their 20s to work and study on the island, the fertility rate in Shimane Prefecture reached 1.46 (sixth in Japan) last year.

衡, which is adjacent to Sendai City in Miyagi Prefecture, is slowing down the pace of the city’s extinction by attracting companies. Toyota Motor Dongil Corp. moved to this small city without even a station in 2012. The population began to increase gradually, increasing from 5,466 in 2010 to 5,870 in 2020. Recently, it has attracted attention again as it has attracted a plant of PSMC, a Taiwanese semiconductor company, and residential housing sites are sold out in an instant.

It was in 2014 that the Japanese government earnestly started efforts to revive local governments. The Shinzo Abe administration started efforts to increase the population of local governments with important policies. The Japanese government’s Population Creation Council announced 896 local governments, or half of Japan’s local governments, as potential cities for extinction.

The “Matsuda Report,” a collective name led by former General Secretary 寛也 増, shocked the entire country. In September that year, Abe appointed Shigeru Ishiba as his first minister in charge of creating local governments. The Japanese government encouraged local governments to come up with ideas on job creation and migration policies and provided them with subsidies.

The effect of the relocation fund has also begun to take effect. 123 people decided to move to the provinces in 2019, and the number increased to 7,806 by 2023. The Japanese government has started to relocate the central government office to the provinces, and until recently, seven organizations including the Consumer Agency and the Cultural Administration have moved to the provinces, and the Japanese government has started to revive the local government by all means.

Nevertheless, there is still a big trend of population decline and concentration in the metropolitan area. Some criticize that it is merely a competition between local governments to take away and take away the population.

With the publication of this decade’s report, the Japanese government called the decline in population and concentration of population in one Tokyo a “strategically challenging task,” saying, “It is necessary to take seriously the region’s difficult situation.”

After all, the target for the government to slow the population decline is the younger generation and women. Their influence is great. They are leaving the province because the province is uncomfortable. But they will not leave the province if there is no inconvenience.

JULIE KIM

US ASIA JOURNAL