South Koreans are known to be among the world’s worst workaholics, ranking second in the OECD in terms of working hours last year.

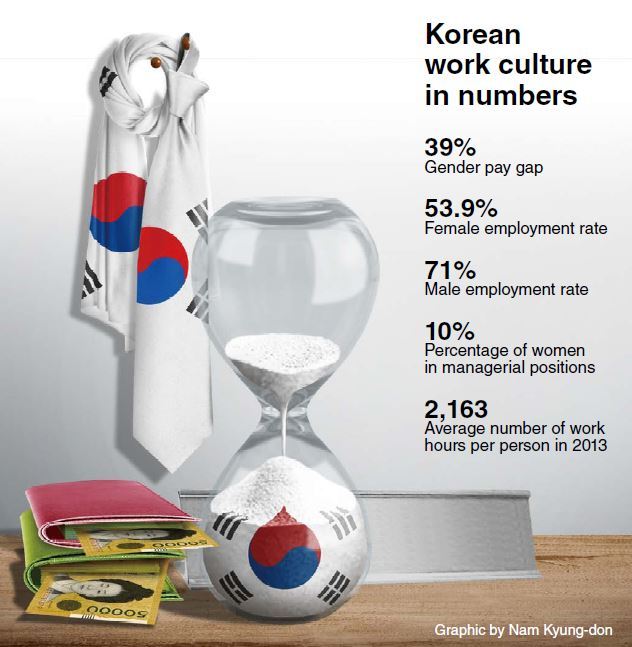

On top of the long working hours ― the average Korean worked 2,163 hours last year, 1.3 times the OECD average ― Koreans often endure forced drinking sessions and work dinners under their uniquely hierarchy-driven work culture.

Experts say this work culture was influenced by the Japanese work values adopted during the colonial period in the early 20th century, as well as the military-driven culture that dominated South Korea under the authoritarian governments of the ’60s and ’70s.

“For example, companies in South Korea and Japan regularly hold sports competitions among their staff, and this is something that is very rare in other countries,” culture critic Lee Moon-won told The Korea Herald.

“It was the Japanese who spread the concept of ‘myeolsabonggong,’ which means ‘destroy your personal life and devote yourself for the betterment of your community.’ The concept encouraged men to sacrifice their personal life for the companies they worked for, and such a life was viewed as ideal and even honorable. Today’s work culture in South Korea certainly has traits that were influenced by this concept.”

This unique corporate culture is one of the factors behind South Korea’s low employment rate among women, as well as its gender pay gap ― 39 percent ― being the highest in the OECD, experts say. Only about 10 percent of all senior or executive positions were held by women here while only 53.9 percent of all Korean women were employed last year.

Kim Soo-mi, a 35-year-old stay-at-home mom, used to find “hoesik,” literally “dinners with coworkers,” particularly painful while working at a sales outsourcing firm. The gatherings often involved heavy drinking as well as visits to karaoke bars ― where she and her colleagues were expected to entertain those in managerial positions.

The hoesik involved multiple rounds and ended at about 2 a.m. despite the fact that she had to show up as early as 6 a.m. the next day.

“Whenever I had to leave early from those dinners because of my daughter, who was 2 at the time, my female boss would tell me not to be a disgrace to women by leaving before it was over,” she said.

“I thought, if I was disgracing fellow women by wanting to be with my daughter at night, I should just disgrace them once and for all by quitting.”

Ahn Sang-soo, a scholar specializing in gender studies, said many Korean women are faced with the need to assimilate themselves to the country’s male-oriented work culture in order to succeed professionally.

“An ideal society would be one where women would succeed without having to undergo such assimilation,” he said.

“Most men learn how to behave around their superiors while doing their mandatory military service. There, they are encouraged to be obedient and not to challenge their superiors, whereas women don’t undergo this experience.

“And when a woman says no to her boss, it is often considered rude or difficult even if she has a valid reason to refuse. But for working mothers who don’t have enough child care support, saying yes to every assignment and hoesik is nearly impossible.”

Ahn said Korean men are also victims of this culture and system, as it destroys their relationship with their families.

“After more than 15 years of working 9 a.m. to 10 p.m., you are more used to hanging out with your staff than your own family. You work and you drink. It’s a vicious cycle,” Ahn said.

A series of studies have proved that long work hours don’t improve productivity. According to data from the OECD, Germans, who worked about 1,400 hours a year on average from 1990 to 2012, were 70 percent more proactive than the Greeks ― who worked more than 2,000 hours each year.

So why are Koreans so overworked? “For every competition, the number of winners is limited,” said Lee, the culture critic.

“This means for every company, the number of those who have the best skillsets are limited, too. For the majority of the people who are not considered exceptional, the way to earn points from your boss is to stay in the office as long as you can.

“This ― not leaving the office until your boss does ― is also considered as an act of loyalty and sacrifice, which is still considered to be ideal in Korean work culture.”

Kim Sook-ja, an official from the Gender Equality Ministry, said performance reviews at work should be more achievement-based, rather than based on seniority or personal connections in the office.

“I think it has to do with the Korean cultural concept of ‘jeong,’ which makes people more generous to those who are close to them, even in the professional world,” she said.

“But obviously this is creating all sorts of problems. We need a more transparent system that lets everyone be evaluated fairly, based mainly on their skillsets.”

By Claire Lee (dyc@heraldcorp.com)