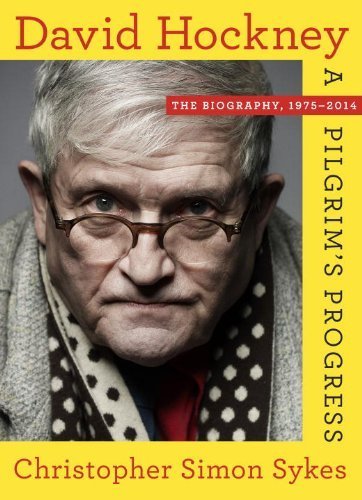

David Hockney: The Biography, 1975-2012

David Hockney: The Biography, 1975-2012

By Christopher Simon Sykes

(Nan A. Talese/Doubleday)

More than halfway through the second volume of his vivid, intimate biography of British artist David Hockney, Christopher Simon Sykes describes the moment in the 1980s when Hockney discovers the creative possibilities of the photocopy machine.

A natural talent who drew from the moment he could pick up a pencil, Hockney falls deeply in love with the density of copier inks ― “the most beautiful black I had ever seen on paper,” he says. “It seemed to have no reflection whatsoever, giving it a richness and mystery almost like a void.”

Sykes, who wrote the book with Hockney’s cooperation, picks up the story of this astonishing artist in 1975, when the working-class boy from the north of England has already won widespread acclaim for his paintings depicting the bright light, azure skies and swimming pools of his adopted city of Los Angeles.

Even greater success lay ahead, including a major retrospective at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in 1988 and a blockbuster show in 2012 at the Royal Academy in London of landscapes he made after moving back to Yorkshire in his late ’60s.

Chapter by chapter, the book unfolds as a series of love affairs, in which the workaholic artist falls madly in love with a new art-making medium ― fax machines, Polaroids and iPads, to name a few ― puzzles over its problems and potential, masters it and moves on. Always, he returns to painting and drawing.

“If everybody is asleep,” Henry Geldzahler, a former Metropolitan Museum curator, observed, “he draws them sleeping, and if he’s alone he draws his luggage lying on the floor. He’ll work until he drops.”

Given his prodigious talent, it’s instructive to see his reaction to the work of other greats such as Picasso and Vermeer: like that of an awestruck schoolboy. A Monet exhibition in Chicago “made me look everywhere intensely,” he says. “That little shadow on Michigan Avenue, the light hitting the leaf. I thought: ‘My God, now I’ve seen that. He’s made me see it.’”

Sykes has an engaging style and an enviable ability to write clearly about art ― including Hockney’s struggle to capture what he once called “our own bodily presence in the world.” But he ought to have given the manuscript another look ― to eliminate clichs, repetitive language and the trivial details that bog down otherwise illuminating diary passages he uses to tell the story of this remarkable man. (AP)