LONDON ― From a Western viewpoint, Dansaekhwa paintings may seem confusing. They don’t fit into familiar key art movements in Western art history.

First created in the 1960s, Dansaekhwa paintings may be in line with minimalism. But behind their simple imagery is much more complex meaning. They resulted from the suppressed freedom of expression that Korean artists experienced under authoritarian governments of the past.

Artist Ha Chong-hyun, 80, recalls his selection of materials, looking at his 1973 work featuring barbed wires.

“I used wires and hemp fabrics a lot for my work. They were two of the most common materials you could find during the time. Barbed wires were frequently used after the Korean War to lock up war prisoners in jail facilities and later to imprison pro-democracy activists. Soldiers put sand in hemp cloth bags to build walls around the military stations,” Ha said in an interview with The Korea Herald on Tuesday.

|

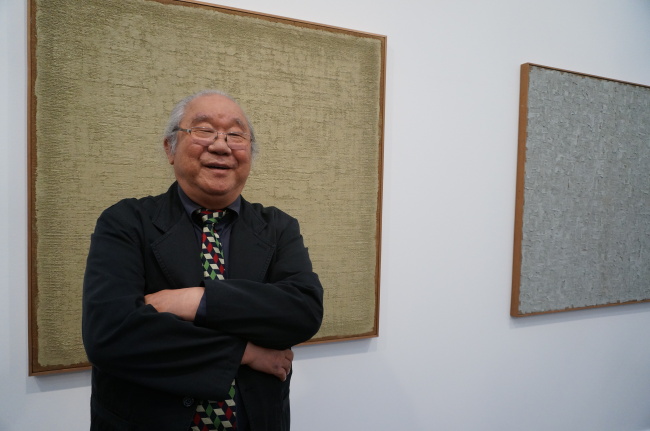

| Artist Ha Chong-hyun poses in front of his painting at the Frieze Masters in London. (Lee Woo-young/The Korea Herald) |

Some artists expressed anger at the suppression in society through explicitly satirical paintings. But artists like Ha chose to stay muted. Instead, he went bold in the gesture of painting. He pushed thick paint through the back of the canvas ― an expression of anger against military dictatorship and of regret for traditional culture disappearing in the process of state-led rapid economic development and modernization.

It was not just Ha who made a rebellious gesture in the form of painting methods. Several other artists such as Lee U-fan, Chung Sung-hwa and Park Seo-bo took a similar approach to paintings. They applied monochromatic paints all over the canvas repetitively or drew pencil lines freely. Some let the paints flow down the canvas while some cut paper or canvas and covered them with paint.

“We didn’t know each other’s work processes at the time. But when we gathered the works from the period later, we found similarities in methods and expressions,” said Ha.

“Dansaekhwa is a miracle, like South Korea’s miraculous economic development.”

Throughout his art career, Ha has sought to try unprecedented practices in art.

He chose materials that others hadn’t thought of and came up with ways to set his paintings apart from others.

Ha has also been at the forefront of changes in the Korean art world.

He led the avant-garde art movement from 1969 to 1973 in Korea. As the head of the Korean Fine Arts Association, he struggled to revamp the then-conservative national art award, which was at the time the only path for artists to debut on the art scene.

“They (established artists) inherited the most conservative concept in art. They weren’t open to new ideas and expressions,” said Ha.

Ha was also an educator who taught arts as a professor of the nation’s prestigious art college Hongik University for 35 years. He served as director of the Seoul Museum of Art for six years.

Ha has been prolific for the past decade, devoting himself to his “Conjunction” and “Post-Conjunction” series ― a milestone series in his Dansaekhwa paintings.

“I will devote myself to promoting the unique Dansaekhwa art movement in Korea and its importance in the world’s art history. That is my last mission as an artist,” said Ha.

By Lee Woo-young, Korea Herald correspondent

(wylee@heraldcorp.com)