“There is no such thing as a good writer and a bad liar,” Amy Bloom wrote in her 1999 short story “The Story,” which remains my favorite of all her work. It’s a vivid bit of double vision, Bloom commenting on the process of storytelling even as she engages in it, and it suggests an edge, a brittle humor that I associate with her. In “The Story,” Bloom describes a widow, coming to terms with new neighbors she calls the Golddust Twins ― until, halfway through, she changes direction, bringing her narrator out from behind the fictive veil.

“I have made the best and happiest ending that I can in this world,” the character (who may or may not be a version of Bloom) announces, “made it out of the flax and netting and leftover trim of someone else’s life, I know, but made it to keep the innocent safe and the guilty punished, and I have made it as the world should be and not as I have found it.”

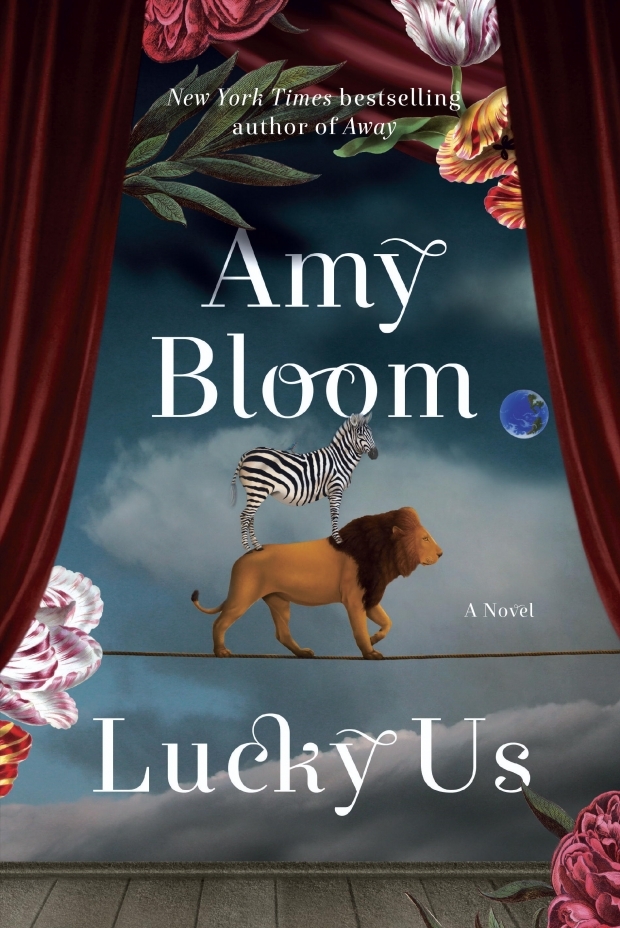

|

| “Lucky Us” by Amy Bloom. (Random House) |

I kept thinking about “The Story” as I read Bloom’s new novel “Lucky Us,” looking for its bite. This is one disappointment of the book, which unfolds with a distressing lack of friction, leaving us with little about which to care. The story of half-sisters Eva and Iris, who end up first in Hollywood and then in Brooklyn after having left their ne’er-do-well father in the early days of World War II, “Lucky Us” is an attempt at an American picaresque in the style of, say, John Irving, or Bloom’s most recent novel, “Away” (2007), which involved a Russian immigrant who literally walks home from New York.

This is not realism, exactly, but something just a bit more heightened, in which naturalism blurs into fable, and the boundaries between reality and dream fade away. “I don’t think the best beginning is loneliness or the memory of a man making you laugh while your sister is kissing his wife in the backyard or the strong feeling that if you do not leap now, unprepared and inept as you are, onto this buckling train, you may be sorry,” Eva tells us, “but I don’t think it’s the worst.”

|

| Author Amy Bloom (Author’s official website) |

What Eva (and Bloom) is talking about is story, which is all we have to shape experience, to create the world as it should be. It’s a point she makes explicit throughout “Lucky Us,” which moves from voice to voice, from character to character, with the elusive texture of a reverie.

Eva and Iris are the center of a floating opera of a household, which includes, after a while, their long-lost father, a gay makeup artist from Hollywood, Iris’ lesbian lover, and a boy, Danny, who they steal (or liberate) from a Jewish orphanage. Late in the novel, Danny and Eva tell each other where he came from: “Danny was born to his mother and father and brother,” the boy begins. “When Danny was very little … his mother died. He was too little to know what happened but Danny had a brother, Bobby, and Bobby said that their mother fell off a roof and their father was so sad and so messed up, he had to take Danny and Bobby to the orphanage, to take care of them.”

Bloom is offering a glimpse of story as creation myth. And yet, unlike the narrator of “The Story,” who recognizes the need to tell stories as a reaction to the messiness, the treachery, of living, the characters in “Lucky Us” rarely are so self-aware.

It’s not that they haven’t been transfigured by tragedy; people die, children are abandoned, there is poverty and betrayal and collapse. Still, the forward movement of the novel is so relentlessly cheery, so much about adversity overcome rather than adversity undertaken, that it all begins to feel a little Horatio Alger-esque.

In part, this is a result of Bloom’s tone throughout the book, which is oddly flat and on-the-surface; she tells this story as if it is already done. That may be unavoidable, given that it takes place in the 1940s, but there is a distance even in the intimate moments that keeps us at an emotional remove.

“I looked for mothers the way drunks look for bars,” Eva reflects, as if to highlight her feeling of abandonment. There is, however, no fallout, no sense of how what she is missing has shaped her, nothing except a kind of native pluckiness, which never seems completely real.

In the end, this is the issue with “Lucky Us”: We don’t believe it, not enough. “I remember some things at a gallop,” Iris writes in a letter, “some moments … bearing down upon me in huge detail, and other things that are no more than small leaves floating on a stream. Memory seems as faulty, as misunderstood and misguided, as every other thought or spasm that passes through us.”

That’s a beautiful passage, and I’d be remiss if I did not point out that “Lucky Us” is full of such observations, so sharp they pierce the heart. Memory, though ― or, in this case, narrative ― needs to be framed if it is to resonate. With “Lucky Us,” Bloom never quite puts the pieces together. Or perhaps it is more accurate to say that her characters, or their story, or the world they live in, lack “the flax and netting and leftover trim” of life.

By David L. Ulin

(Los Angeles Times)

(MCT Information Services)